When everything is a subscription, what do you own?

NOTE: This article is partly a rant, partly a call to the individual for action.

The other day, I got a bill from both Apple (iCloud+) and Google Cloud. It wasn’t anything exorbitant but made me ask “How much am I actually paying in digital subscriptions every month?”.

When I looked, the number surprised me: I was spending around $196/month — and that’s not including tools I’ve probably forgotten about.

A big chunk of this is due to an EC2 instance on AWS that I use for compute. But even without that, I’m still paying $103/month, or $1,236/year, just on digital services.

To put that in perspective, that’s half the median annual income in Thailand, a quarter in India, and about 15% in Vietnam.

$1,200+ to access to opaque, rent-seeking tools and services that I often don’t have the permission to control or even verify/audit. Ironically, they somehow have every permission to surveil me in the name of verification and even harvest my data to sell without even compensating me for it.

The Core Frustration

If there’s one thing you should know about me, it is that I hate subjugation and deeply value freedom and ownership. Therefore, I hate renting proprietary software.

If I’ve already paid for something, I don’t want to be locked out of it with monthly fees, forced upgrades, or cloud dependency.

To be clear, I’m not against paying for what I use.

For example, compute, storage, bandwidth — these have real costs. But a lot of what we’re paying for today is no longer value creation or exchange, it’s straight up extortion. Or more mildly, value extraction.

Allow me to illustrate with some examples:

-

FTC’s action against Adobe. Evidently, Adobe thinks innovation in business means charging consumers for not using their products. Ngl, innovative for sure.

-

X/Twitter Premium. Thanks to Musk, anyone can buy verification for a monthly fee (around $8), regardless of credibility or identity.

Algorithmic reach is heavily throttled for non-paying users. Tweets from non-blue users are de-prioritized or hidden in replies.

Therefore, you must now pay simply to be seen.

Basic functionality like two-factor authentication via SMS was removed for free users — a security feature now locked behind a paywall.

Meanwhile, the advertising model remains, meaning Twitter is now trying to extract value from both ends: users pay to speak, and advertisers pay to mine them.

What does this incentivize? Musk has effectively:

- Undermined trust by turning credibility into a purchase

- Introduced pay-to-play dynamics where paying users dominate discourse (hence, scams as a business work very well with ads)

- Degraded the baseline product for non-payers to make subscriptions look necessary

-

Sony’s PS+ Subscription. Let’s start with the fact that Sony takes a 30% cut of any purchase made through their Playstation store.

So, to them it is not enough that you’re paying to buy their console, then paying them a 30% tax for purchasing a game to play on that console.

Hence, they decided to add a PS+ subscription charge for online play, so that they can make sure that even after you’ve paid for the console, the game, and your internet connection — you still can’t enjoy your game without paying them recurring rent just for existing.

The pattern is clear and this is the norm now — corpos are turning into digital landlords.

We’ve entered an era where the companies which used to be innovative and consumer focused have turned into giant rent-seeking, opaque oligopolies conducting unfair trade practices.

But how are they getting away with this anyway?

To quote the Scottish dude who was into economics:

“It is the maxim of every prudent master of a family, never to attempt to make at home what it will cost him more to make than to buy.” — Adam Smith

So, if things are the way they are for the reason that is “economics”, wtf is this article for anyway?

Well, because economics also enables competition. And I believe we’re entering the golden era of enshittification of tech.

And as one of our billionaire overlords put it:

“Your margin is my opportunity” — Jeff Bezos

So, what can we do about it?

Well, there’s two parts to that. As an individual you can make a change both on a personal level and on a societal level (by building better products and services). Here’s how:

1. Personal Shift: Opt Out

Start with a personal experiment in digital sovereignty.

You don’t have to rage-quit the internet, but be more intentional in the way you’re using some of these technologies.

Try to be more conscious about the tools you use, and where you place trust. For me, it means:

-

Auditing the tools we depend on.

-

Replacing rent-seeking black boxes with open-source, local-first, or p2p alternatives when possible (you’d be surprised what you can find, if you just looked).

-

Supporting creators who respect user agency and transparency.

-

Contributing to open source — this doesn’t mean you have to write code. Reporting issues on GitHub, donating funds to an open source project you’re actively using or even just advocating for others to make this shift helps move things forward in the right direction.

With that said, most people are lazy enough not to do any of that. And, that’s where your opportunity lies. So, let’s move to the next part.

2. Business Opportunity: Appetite for Disruption

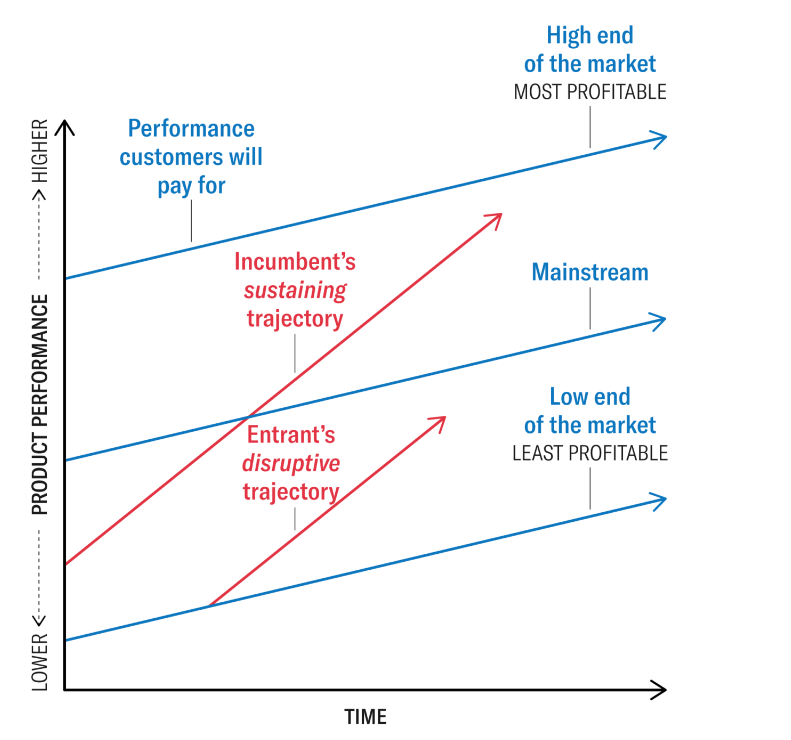

Disruptive Innovation describes a process by which a product or service takes root in simple applications at the bottom of the market—typically by being less expensive and more accessible—and then relentlessly moves upmarket, eventually displacing established competitors. — Source

This is the hard, unsolved part. But that’s why this is also the juicy, exciting part.

I believe that certain parts of the big tech industry are ripe for disruption now. The principle is to offer affordable solutions to overlooked market segments.

The thing that big tech fears and refuses to touch — forks, interoperability, composability, user control — is the exact thing that makes open source so powerful. It invites participation. It turns users into contributors. It fosters meritocratic ecosystems where the best ideas rise because they’re open to evolution.

Take Linux for example. It started out from a similar frustration Linus Torvalds had against UNIX — it was proprietary and expensive.

The best available alternative at the time was Minix, a small teaching-oriented Unix clone developed by Andrew Tanenbaum — but it had limitations and wasn’t truly open for modification.

So Linus started building his own kernel.

He posted this on the comp.os.minix newsgroup on August 25, 1991:

“Hello everybody out there using minix –

I’m doing a (free) operating system (just a hobby, won’t be big and professional like gnu) for 386(486) AT clones…”

That hobby kernel would later become Linux.

It started by serving an overlooked group: Power users and students who wanted a free, modifiable UNIX-like OS.

Overtime, it grew to power most of the internet (servers, containers, routers), android phones, supercomputers, NAS boxes, embedded systems, developer laptops.

More recently even PewDiePie switched to Linux.

Will it become the norm for consumer desktops? I don’t know, but clearly in many significant markets Linux has already won.

Today, there’s a small market segment of power users like myself who are tired of being farmed. They don’t want dark patterns, forced subscriptions, or “cloud lock-in” disguised as convenience.

They want products that work, that can not just be trusted, but verified, that don’t spy on them in the name verification and security, and that can be extended, upgraded or run locally if needed.

These individuals have two key characteristics which make for a very loyal and valuable customer base:

- Disposable income

- Deep seated issues with authority

This is where I feel open-source codebases, user-upgradable hardware and technologies like blockchain can shine.

By realizing that:

- There’s a (relatively) small, underserved market of open-source advocates and privacy loving enthusiasts who really value ownership.

- The true frustrations of these users include forced recurring costs (no path to ownership), loss of control, closed ecosystems and lock-in, artificial friction and apathy from incumbents

How to build a business using these realizations?

When you understand these root frustrations of this underserved user base and the structural rot in big tech’s incentives — a roadmap for building becomes clear.

You’re building for people who are willing to pay for autonomy. This market is almost actively repelled by the direction mainstream software has taken.

In such environments, the right product doesn’t need scale to thrive because the loyalty is so strong. It simply needs to align with the values:

- One-off payment structure, with optional future add-ons/upgrades

- Incentive alignment for both open-source contributors as well as the users

- Self-hosting licenses

If the opportunity is so obvious, how come someone hasn’t built this?

Well, that’s because of the hard part: Network effects.

Unfortunately, there’s no such thing as a free lunch — if you wish to capitalize on these potentially huge opportunities, you will need to find a wedge that breaks the existing network effects patterns. If I had a clear insight on even one of these wedges, I would probably not be writing this article to begin with.

So far, there have been several attempts at solving these problems — especially in the web3 space — but none have figured out quite the right formula yet.

Most have been too consumed by redundant/scammy tokens launches, delusional idealism and straight up horrendous user experiences.

But that’s where lies your opportunity.

Using the resources and technologies like AI, blockchain and other buzzwords we have today, it is possible to build better systems. And whoever figures out how will make generational wealth doing so.

I intend to cover some industries that I think are ripe for disruption in a future article and outline the key problems I’ve noticed (but no promises).

In Closing

We don’t need more hype. We need better defaults.

This isn’t about replacing every tool with an open-source clone or living in the woods syncing our to-do lists over LAN. It’s about asking better questions:

- Do I really own the tools I depend on?

- Am I comfortable with how my data is handled?

- Do I feel respected by the platforms I support?

And if not — can we build something better?

The answer is yes. But it won’t come from billion-dollar incumbents or Web3 grifters trying to slap a token on everything. It’ll come from users turned builders — who got frustrated enough to do something about it.

So if you’re a user: start opting out where you can.

If you’re a builder: look for the cracks. If you haven’t found one yet, keep looking.

And if you’re tired of being farmed: you’re not alone.

We’re not early anymore. The time is now.